Peter Bayne and Pat Coleman

One of the most intriguing Inuit testimonies relating to Sir John Franklin's last expedition is one that was purchased by Canada's Department of the Interior back in the late 1920s and is referred to as the Jamme Report or, more commonly, the Peter Bayne Story.

The fact that this story did not surface for more than sixty years after it was first told, and that it came attached with a price tag, has raised the eyebrows of many historians. In its defense, however, the story involves some unusual circumstances that help to explain its late introduction.

In the spring of 1866, Charles Francis Hall and a group of Repulse Bay area Inuit were camped out on the ice along the southwestern shore of the Gulf of Boothia, which was known then as the Sea of Ak-koolu.

It was there that they were met by a group of Pelly Bay Inuit who set up camp alongside them. During this encounter, Hall met a young Inuk hunter named Supunger, from whom he collected testimony of a journey he and his uncle had made to Ki-ik-tung (King William Island) three years prior.

While the two groups interacted, the Pelly Bay Inuit learned of Hall's intent to travel towards Ki-ik-tung and warned him that the Inuit of that area were fierce and protective of their hunting ground and would kill anyone found travelling upon their land. These warnings were not taken lightly by the Repulse Bay Inuit and Hall was ultimately forced to abort his planned mission. Supunger and his family remained behind with Hall and his group for the remainder of that spring, and it was during this time that Hall conducted a number of interviews with both him and his wife and was able to record the story of the stone vault that Supunger and his uncle had seen on King William Island.

Hall and his group returned back down to the Repulse Bay area to what was then known as Rowes Welcome. The "Welcome", as it was called by the whalers, had become a popular winter harbor for whaling ships that had had an unsuccessful season or wanted to get an early start the following year.

As a solution to his problem, Hall hired five men from the ships. This small party of armed men would then be able to provide the protection needed to complete Hall's quest to reach King William Island. It was in the fall of 1867, after the whaling season ended, that Hall interviewed and signed one-year contracts with Frank Laylor of Bangor, Maine, John S Spearman of Quebec, Jose Francis from the Azores, Patrick Coleman from Dublin, and Peter Bayne from Nova Scotia.

The men were all assigned specific duties prior to making the overland expedition, and so it came to be in the spring of 1868 that Hall gave both Patrick Coleman and Peter Bayne the task to hunt and place meat caches up towards Committee Bay, which was Hall's intended route to King William Island.

Bayne and Coleman were accompanied by a family of Inuit and, about sixty miles north of Repulse towards Committee Bay, they encountered a group of Inuit that had travelled down from the Boothia Peninsula. The two parties camped together and Bayne, who proved to be a good hunter and had already made several meat caches, offered to share some of their catch with the strangers. It comes as no surprise that Bayne's action then set the stage for the open communication and for more testimony to be told.

According to Bayne, it was actually Coleman who got the most excited about hearing an eye- witness account from the elder of the group (and I cannot help but think this must have played a key role in the fatal conflict he would later have with Hall). A full account of the story can be found in Appendix C, Canada's Western Arctic, Department of the Interior, Report on Investigations in 1925-26, 1928-29, and 1930, printed in Ottawa by F.A. Acland in 1931.

In general, the story relates actual events. The two ships were locked in the ice and the white men had established a camp on the shore with a number of tents, and that one of the tents, the largest one, had many sick men inside it and the men who died were buried on the hill in behind the camp. One man, however, died on the ships and was brought to shore but not buried in the ground like the others; he was laid to rest in an opening in the rock which was covered with something that turned to "all the same stone", and many guns were fired.

Knowing that this new information was important, Bayne and Coleman convinced the Inuit party to return with them to meet Hall and retell their story. Unfortunately, Hall had left the camp and headed north towards the Fox Basin where recent news said that white man footprints had been seen in the area. With Hall being gone, it was decided to have the story retold to everyone at the camp and this was done by holding a "plenty tea" where all attended. The details of the story remained the same with the exception that there was more than one stone vault constructed: a large one and several smaller ones.

Naturally, when Hall returned to camp, the men were excited about giving him this new-found information. Surprisingly, Hall reprimanded the men for their actions. Offended, they soon lost interest in Hall's quest and a conflict arose between Hall and Coleman. It ended with Hall shooting Coleman, who died fourteen days afterward.

After Coleman's death, the remaining four men hired by Hall boarded the first whaling ship to return, and the story seems to have become a silent one. Hall does not mention the story in any of his journals; he only tried to justify the shooting of Coleman by saying he was being threatened and that Coleman was mutinous. The following year, Hall did succeed in reaching the southeastern coast of King William Island but then he simply turned around and headed back. Why he ended the search when he was so close, and after so much effort, no one will ever know.

Peter Bayne was originally from Nova Scotia and at the age of twenty had enlisted in the Navy and served in the American Civil War as a sailor on the USS Commodore gunship Barney in 1864. After the war ended, Bayne found work on board the whaler Ansel Gibbs and this is how he came to be in Repulse Bay at the same time as Charles Francis Hall.

After the shooting of Coleman, Bayne returned to the United States where he eventually ended up in California and was married in 1878. Bayne and his wife later settled on a farm in Dryden, Washington where they had two children. Sometime around 1887, Bayne decided that he would return back to his whaling profession and left his farm and family to go north to Point Hope, Alaska. During his absence, his wife filed for divorce on the grounds of desertion and then married a neighbor. Bayne, who apparently only found this out upon his return, argued that he did not desert his family and that his wife had agreed to him returning to his old whaling profession. For a time, there was an ongoing legal dispute over the matter, until a judge ruled on the divorce and also awarded the farm to Bayne's ex-wife. The dispute ended quickly when his ex-wife died during childbirth, and the court placed his two children in the custody of their grandparents.

It's not known exactly when, but Bayne did return to Point Hope, and his reputation there could be called questionable. Charles Brower, known as the "King of the Arctic", who personally knew Bayne, wrote in 1888 that Bayne was a "corrupt shore whaler". Bower blamed him for teaching the natives how to make "hooch" from flour, sugar and molasses, which resulted in all the villages along the coast having one or more stills in operation.

Based on what little information we have, there is no question that incidents surrounding Bayne were "shady". He found himself getting arrested in 1892 pending an investigation on his involvement with Captain Gilbert Bennett Borden (the superintendent of the Whaling Station located at Cape Smyth, about 11 miles south of Point Barrow). It is not clear as to whether Bayne was convicted on any charges and there is no other mention of him until an article appeared in the Oregon News on April 26, 1913. Bayne, now 69 years old, had just purchased a schooner named the Duxbury and was planning to sail it to King William Island. He claimed that he was expecting to find the lost Franklin vault and that it would be located in a 20-mile stretch along the Island's western shore.

Three years later, on May 8, 1916, another newspaper article appeared, this time in The Spokesman Review. It announced that Captain Peter Bayne and his new bride were shortly setting sail for King William Island, again to search for the stone burial vault of Sir John Franklin. Bayne was now 72 years old and it is not known if the voyage ever took place or was even attempted. What is clear is that sometime from that time up to Bayne's death in 1926 he befriended George Jamme, a mining engineer, who lived in both Seattle and Lost River, Alaska.

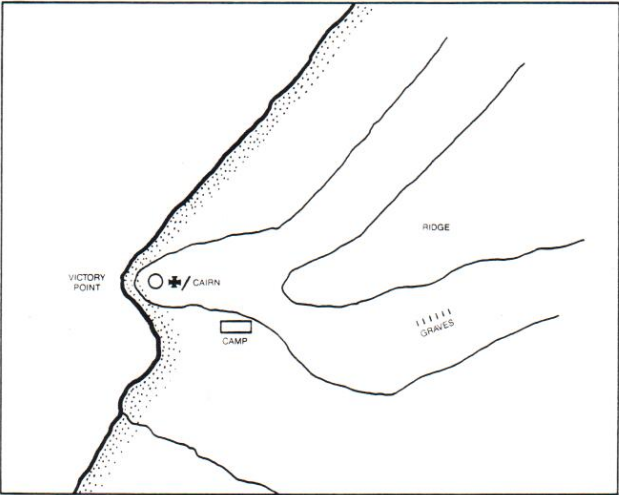

The Bayne story gives us some fairly simple details of where this camp may have been located, however if we also consider the needs of the expedition we may find that there are actually very few places that suitably match.

Bayne confided in Jamme and shared the story of the Franklin vault and his hope to have had the opportunity to search for it. Bayne must have been well into his 70s and visiting King William Island had now become something out of his reach. We also know that Bayne had a map showing the location of the site, but that map was lost and the one we currently have was redrawn from memory.

After Bayne's death in 1926, the story remained in the hands of George Jamme, who later passed it on to a Judge T.W. Jackson of Vancouver. In 1929, Jackson attempted to sell the document to the Canadian Government for twenty-five thousand dollars. The Department of the Interior reluctantly paid Jackson one thousand dollars for what they called the "Jamme document". In 1930, Major L.T. Burwash, who had been in the area investigating the health status of the Inuit (as well as wildlife and geology), was then tasked with following up on the story by completing an investigation of the area around Victory Point in hope of finding the vault. Nothing fitting the description given in the Jamme Document was ever located by Burwash.

Although the story has been subject to much controversy, it has been the backbone of my search for the past 24 years. I have added the name of Patrick Coleman to the expedition's title, as I believe that if Coleman's life had not ended as it did, he would have persisted in following up on the story any way he could.

I have always believed that Supunger's testimony and the Bayne / Coleman story were related. One was from a witness to the actual events (which presumably happened in the spring and summer of 1847), the other was an observation of what remained of the site fifteen years later. There are, however, a number of discrepancies that prevent the stories from fitting together as they should if they were describing the same sites. This is the reason I now speculate that there are actually two burial sites, located over thirty miles apart. The one relating to Jamme Report is the burial vault of Sir John Franklin and the crew members who perished between September 1846 and August 1847. If this is so, the Supunger site can only be the burial vault of Lt. Graham Gore along with the graves of the crew members that perished sometime between September 1847 and April 1848.